|

Fritz Lang Biographie:

Birth Name: Friedrich Christian Anton Lang

Born: December 5, 1890, Vienna, Austria

Died: August 2, 1976

Education: Technische Hochshule (architecture); Vienna Academy of Graphic

Arts (art); School of Arts and Crafts, Munich (art); Academie Julien,

Paris Human Desire (1954), made during Fritz Lang's last decade as a

film director, begins with an emblematic image: a locomotive rushes

forward, swift and dynamic, but locked to the tracks, its path fixed,

its destination visible. Like Lang's films the train and the tracks

speak of a world of narrowly defined choices. The closing image is even

more severe: survivor Glenn Ford departs, his locomotive passing a sign

on a bridge. Ford does not see the sign, but we do; abbreviated by intervening

beams we suddenly see "The world takes" just before the film ends.

This vision of a hostile universe, constraints on freedom and messages

that are missed or misunderstood but always seen by someone, can be

found in all of Fritz Lang's films. His work has a consistency and a

richness that are unique in world cinema. In Germany, in France, in

Hollywood, then in Germany again, Lang built genre worlds for producers

and audiences and veiled meditations on human experience for himself.

Lang's vision is that of the outsider. James Baldwin, an outsider himself,

catches Lang's "concern, or obsession...with the fact and effect of

human loneliness, and the ways in which we are all responsible for the

creation, and the fate, of the isolated..." Born an Austrian, Lang fled

his training as an architect for a jaunt through the middle and far

east, returned to Paris just in time for the beginning of WWI, then

fought on the losing side of the war. Recovering from wounds which cost

him the sight in his right eye, Lang wrote his first scenarios: a werewolf

story which found no buyers, and Wedding in the Eccentric Club and Hilde

Warren and Death, which were sold and eventually produced by Joe May.

May's deviations from Lang's scripts motivated Lang to become a director

himself; his first movie was Halbblut/The Half-Caste (1919), a still-lost

film about the revenge of a half-Mexican mistress. Later that year he

directed the first film of a two-part international thriller called

The Spiders (1920). Part one, subtitled The Golden Lake, proved so popular

that his producers insisted Lang immediately make part two, The Diamond

Ship. He had been working on another script which he hoped to film,

so he reluctantly gave up The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari (1919) to Robert

Wiene. His contribution to that landmark film nevertheless was crucial:

Lang thought up the framing device, in which it is revealed at the story's

end that we have been watching a tale told by a madman, thus significantly

undercutting the audience's perceptions of the story.

Lang's career in the 1920s was one of spectacular rise to fame. With

each film, he became more assured, garnering critical acclaim as well

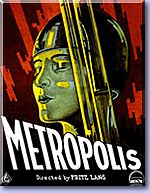

as a popular following. Dr. Mabuse the Gambler (1922), Die Nibelungen

(1924), Metropolis (1926), and Spies (1928) are among the greatest silent

films produced anywhere. Lang also made a remarkable transtition to

sound, with M (1931), but he ran afoul of Nazi authorities with The

Last Will of Dr. Mabuse/The Testament of Dr. Mabuse (1933), whose villains

mouthed Nazi propaganda. When the film was banned and Lang was requested

to make films for the cause of the Third Reich, he immediately fled

Germany, leaving behind most of his personal possessions, as well as

his wife, screenwriter Thea von Harbou (who had joined the Nazi party

and become an official screenwriter).

Lang made one film in France, then moved on to Hollywood, where he spent

the next 20 years working in a variety of genres, mainly thrillers (e.g.

Man Hunt, 1941, Scarlet Street, 1945, While the City Sleeps, 1956) and

some outstanding westerns (The Return of Frank James, 1940, Rancho Notorious,

1952). Tired of warring with insensitive producers, Lang left the U.S.

in the mid-1950s to make a film in India and then returned to Germany

for his last set of films, including a final chapter in the Dr. Mabuse

saga.

The disorienting frame in Caligari is an important part of Lang's distinctive

vision. His films are punctuated by shifts of viewpoint and discoveries

which transform the reactions of his characters - and of his audience.

The most obvious of these shifts of viewpoint come in Caligari and The

Woman in the Window (1944), in which the drama is suddenly revealed

to be a dream. But they also occur in the Mabuse films; in M, with the

policeman mistaken by a burglar for another thief; and in The House

by the River (1950), when a servant is strangled because another maid

appears to be responding to her cries for help.

Lang's films are also about contingency, the recognition that extra-personal

forces mold our lives, shape our destiny in ways we cannot predict and

only somewhat modify. In the two-part film, Die Nibelungen, Kriemhild

is transformed from a secondary figure in the first film (Siegfried)

into a whirlwind of fury in the second (Kriemhild's Revenge). Even the

characters in the film are shaken by these transformations. The king

of the Huns is staggered by Kriemhild's thirst for death; the vengeful

underworld in M that has captured and tried Peter Lorre is taken aback

by Lorre's confession that he "must" rape and murder, that he is something

of a spectator to his crimes.

These moments of perception are the foundation of Lang's importance

and continuing strength as a filmmaker. They constitute a kind of morality

that he never abandoned. In the script for Liliom (1934), his French

film made after he fled the Nazis, Lang wrote, "If death settled everything

it would be too easy...Where would justice be if death settled everything?"

Thirty years later, playing himself in Jean-Luc Godard's Contempt (1963),

Lang wrote for his character, "La mort n'est pas une solution." ("Death

is no solution"). Nor does death erase human striving. In Between Two

Worlds/Der Mude Tod/Beyond the Wall/Destiny (1921) the force of love

survives, in Fury (1936) the cycle of vengeance is broken, in Clash

By Night (1952) Barbara Stanwyck chooses reponsibility, in The Big Heat

(1953) Glenn Ford finally turns to the police and ends his vendetta,

and in Human Desire Ford again leaves the scene of the crime, choosing

life over the locus of death.

Biography from Baseline's Encyclopedia of Film

|

|